How to (Finally!) Share Our Views with Trump Voters

Hint: Fewer Facts, More Stories

Programming Note: This concludes my deeper dive into the steps of the Smart Politics Persuasion Conversation Cycle, as developed by our founder, Dr. Karin Tamerius. The Cycle is the core of our hands-on Smart Politics work—it’s what we teach folks to carry out more productive and (as the name suggests) persuasive conversations with folks we disagree with, for example Trump voters.

If you haven’t already, check out the first four steps, Ask, Listen, Reflect, and Validate.

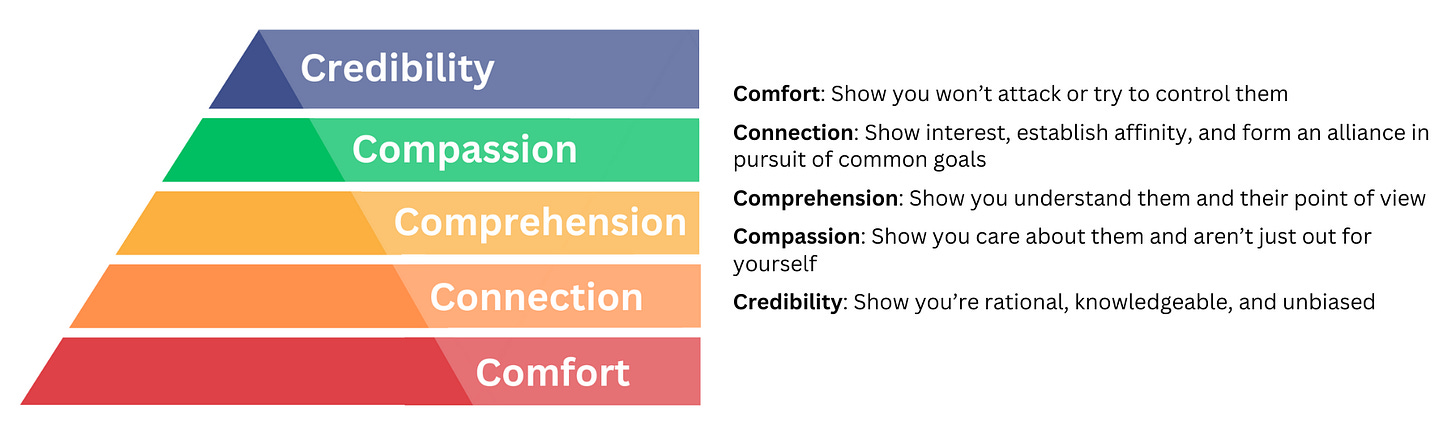

These Cycle steps are part of a larger process designed to help teach folks the “how-to” once they’ve decided to try this work, to try to have these kinds of conversations. If you’re new to Smart Politics and this is the first piece you’re seeing, learn more about how the Persuasion Conversation Cycle works to build the Trust Pyramid:

Step Five of the Persuasion Conversation Cycle: SHARE

I sometimes flippantly say, “Feelings don’t care about your facts.”

I know it’s glib—yes, of course there’s a place for sharing facts in Smart Politics work, but it comes at the end of the conversation, not the start. A core tenet of Dr. Tamerius’ Smart Politics philosophy is this training and work is designed to break us of our lifelong habits of wanting to lead with facts, figures, sources, logic, reason, and debate-class arguments. Karin created this Persuasion Conversation Cycle to flip things around—to build muscle memory around holding the “facts” until last, not first.

We know it’s not easy. We’ve been listening and reflecting and agreeing for what feels like forever, maybe having to go back over and over, repeating the earlier steps. And we may have heard some outrageous or frustrating, even triggering things from the other person. We’ve held our tongue and now we want to pour it all out, tell it like it is. I still catch myself wanting to jump right into conversations with “But you know…” or “Actually…” or “Well, I think…”

But just because we’ve gotten to the last stage of the Cycle, now is not the time to slip back into those old, bad habits. Even when following the steps, we still sometimes get to Share, get excited and eager, and mistakenly start making arguments, using reason, and offering up evidence and facts to show the other person they’re wrong.

As we’ve been saying throughout this series, the human belief defense system is tricky—most folks will not listen to, hear, engage with, or accept our facts until we’ve connected with them enough to lower those defenses. Whenever we try to present reasoned argument, the other person’s defense system is going to kick in, even if we’ve earned their trust and built a great relationship. If someone feels we’re still mounting an attack on their carefully curated beliefs, their trust in us is going to begin to crumble.

Remember the Trust Pyramid? That’s what we’re trying to build (or climb, choose your metaphor): Getting the other person to a place where they trust us enough to actually hear what we have to say. And that’s why we save the Share step for last.

The Power of Story

Now that we’re finally at the end of the Cycle, the catch is we’re still going to ease off arguing and debating too heavily with cold, hard facts and reason. Rather than throwing big binders of facts and sources at them, the most basic and effective way to introduce our perspective into the conversation is through storytelling. We want to couch our facts and opinions in as personal and narrative way as possible, using stories that continue to connect on a human level. The emphasis remains on maintaining the connection we’ve been building all along.

So instead of making an argument, it’s much more powerful and effective to share an anecdote that relates to the topic. For example, if we're talking about climate change, instead of presenting someone with a bunch of facts and figures about why climate change is happening, we share a story about how we or someone we know has personally been impacted by recent changes in climate patterns.

Our Brains Are Wired for Stories

Stories bypass the rational part of the brain. Unlike cold, hard data which stimulates the analytical part of our brain along with the belief defense system, stories can evade psychological defenses and bypass resistance, tapping directly into our emotions, memories, and senses.

Stories are memorable. Statistics and data is usually quickly forgotten, but when our systematic nervous system is fired up by the emotions of a story, we more easily absorb and remember new information. When you think of a past conversation with someone, how often do you remember a story they told you about their experiences versus how well you remember a fact or statistic they presented? In fact, psychologist Jerome Bruner found that information presented in narrative form is up to 22 times more likely to be retained than raw data.

Stories elicit empathy. When we hear a story, our brains activate and connect with the other person more deeply and emotionally—we feel what it’s like to walk in their shoes, to experience their life with them. (That’s why Roger Ebert famously called movies “empathy machines.”)

Stories aren’t debatable. Once we’ve built that Trust Pyramid, when we share a personal story it becomes harder for someone to dismiss or deny it like they can facts. They can always question our sources and facts, but when we tell them what happened to us, share our lived experience, it’s more difficult for the other person to easily dismiss or ignore.

Types of Stories to Share

Several types of stories work well in conversations:

Something That Happened to Us: The best stories are drawn from our own life and experience. In fact, it doesn’t hurt for us to sit down ahead of time and think over the most pressing issues of the moment: Immigration? Climate? Gun control? Reproductive health and rights? Social safety net, healthcare? Racism, sexism, anti-Semitism, anti-LBGTQ? Authoritarianism, fascism, corruption, genocide? As we look over our list, is there a personal story or angle we can share for these issues?

Something That Happened to Someone We Know: Not all of us have our own personal story about every topic, but we may know others—loved ones, friends, family—who’ve had a powerful experience around some of those issues. We can even share news stories about how policies affected specific individuals, emphasizing the personal impact over policy points.

We Used to Think That Way Too: Maybe we once held some opinions that skewed to the middle or right on some issues but have since changed our mind. Sharing our personal journey on our way to a more progressive understanding can be influential: “I used to think…” “In the past, I didn’t really understand…” “Over time, I’ve met people who helped me see and open up to new perspectives…” “I’ve come to realize that…”

When sharing, don’t go a step too far. A mistake we sometimes make in this step is turning our story into an argument by tacking on a reasoned conclusion. If we find ourselves saying something along the lines of, “Therefore, we must...” we’ve strayed back into Belief Defense System territory that will likely cause the other person to shut down or argue back. Instead, trust the process.

The power of stories is people draw their own inferences without us adding an explicit moral or sharpened point. If our story is powerful, effective, and well-told, the other person will figure out the point for themselves.

When We Really Want to Share Some Facts

We’re not saying throw away all stats and figures, facts and sources, but think of them as a very powerful spice or hot sauce—a few drops go a long way and should be sprinkled in sparingly, preferably near the end of a personal story. And when we do feel the opportunity is right to share some facts, we can still soften the edges by maintaining a gentle, humble tone: “It’s my understanding that…” “I’m no expert on this, but I’ve read that…” “I guess what I’m wondering is…”

We can also tailor the sharing of facts to who we’re talking to and their learning preferences. The tricky part of the entire Persuasion Conversation Cycle is that ultimately we are unique individuals talking with other unique individuals. Yes, we want to practice the Cycle and make it conversational muscle memory, but this work still ends up as much art as science. So yes, sometimes we may be talking to folks who really want and respond well to facts and sources—they may prefer that to our anecdotes.

That doesn’t mean we can skip the previous four steps in the Cycle—they are still essential to building trust and connection. It’s through asking and listening that we may understand more about how receptive the other person may be to a little more (still careful! still gentle!) sharing of facts, figures, stats, and studies.

When We Really Want to Share a Resource

In addition to carefully judging if it’s okay to share facts with someone who seems open to them, we may want to share resources with the other person; articles, videos, podcasts, films, books, etc. In general, it’s better to avoid doing this too much, but if we really want to, all the same guidelines apply: politely and gently, and only after building trust and connection.

Plus, it really helps if we ask for their consent before sharing a resource. As in all things Smart Politics, don’t go charging in while pushing something on them: “Listen, you really need to read this book, it will open your eyes, change your views, rearrange your ideological sock drawer…” That’s likely to create a defensive reaction, especially if they feel us pushing our resources is an attempt to control them.

Instead, gently ask for their permission: “Thanks for helping me better understand where you’re coming from on this issue—I think it’s important we understand each other better, and sharing information can help with that. I read an article that really had an impact on how I view this issue, and I was wondering if you’d be interested in reading it? I feel it does a good job presenting things from my perspective. Is it okay if I share it with you?”

Onward!

We’re at the end of our tour of the Persuasion Conversation Cycle, and we know what that means: Time to go back to the top and start all over again at “Ask”! One conversation, one trip around the Cycle is probably not going to do it—we’ll likely need to keep asking and listening, reflecting and validating, circling back through the Cycle again and again across multiple conversations. Over weeks. Months. Years.

Deep down, we all hope the people we talk with will suddenly see the light and change their opinion. That sometimes happens, but it’s rare. Think of ourselves as farmers planting a crop: No matter how compelling our story, most of the time we’re sowing seeds that might take root and one day blossom into changes—but we won’t know until later if our efforts paid off. Sure, we want to see the mighty oak tree, but we’re all starting with a handful of acorns. Patience, diligence, and repetition is how we must approach both the steps of the Cycle and the overall goals and results of this long-term work.

What is the Smart Politics Way?

Smart Politics encourages and teaches progressives to have more productive conversations with Trump voters. We believe the most effective actions for achieving short- and long-term progressive goals involve talking one-on-one with and listening compassionately and constructively to folks with different opinions.

More on our work:

Want to learn more about Smart Politics and get involved?

Every Sunday night (and some Wednesdays), we meet on Zoom to teach, share, and support one another. Sign up for email recaps and reminders about these weekly calls

Locke Peterseim is the Smart Politics Content Manager.

Just shamelessly borrowed from this and other Smart Politics content for an upcoming presentation I'm doing about MAGA cult deprogramming to some local activist groups. Thanks for everything you do. You have one of the best resources out there on how to actually reach out to MAGA voters and bring them back to reality. We can never heal this nation by fighting them we must win them back. Everyone is persuadable if you're willing to do the work!

Typo - "core tenet", not "core tenant"

The problem here is that if it's a matter of dueling stories, why should the truthful amateur's story win over the professional liar's story? By definition, the professional liars are going to be much better at it, since it's what they do all the time. I'm aware this question may not have a good answer.