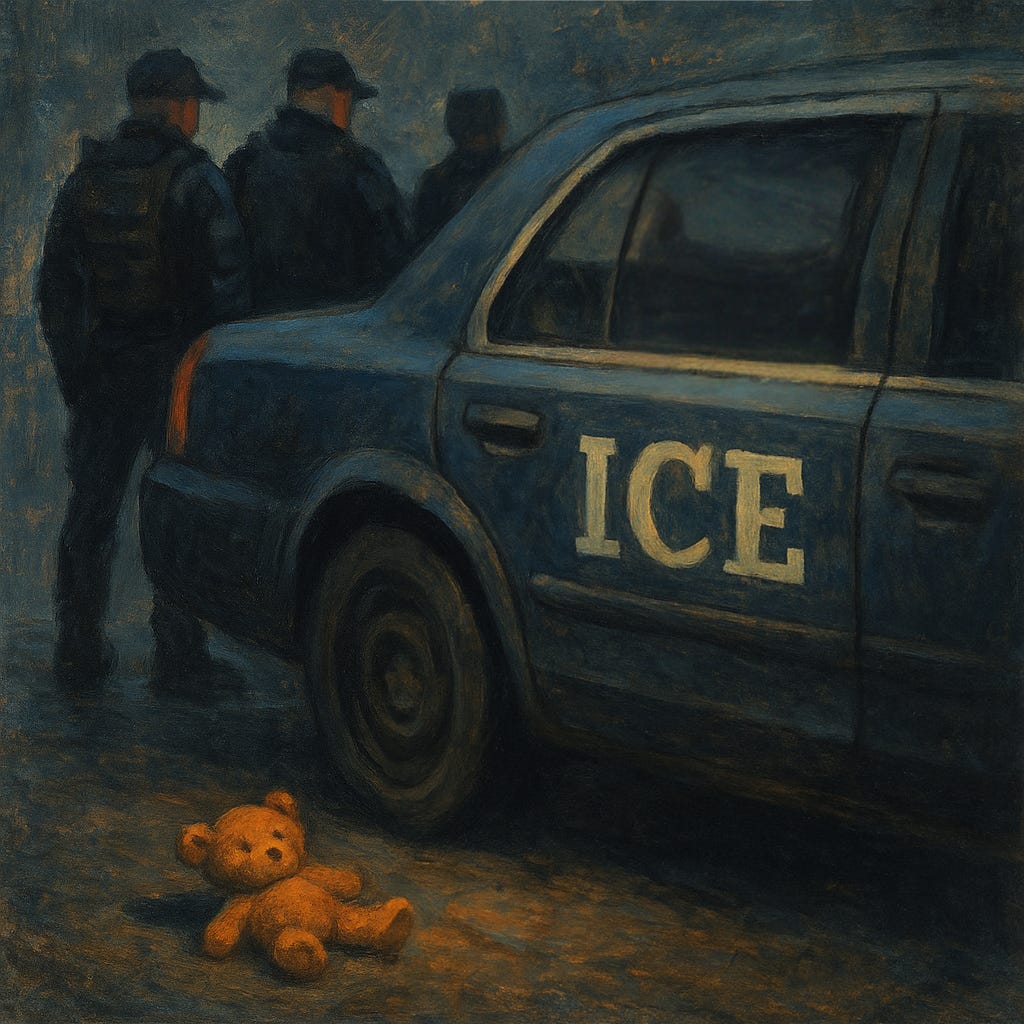

On April 25, 2025, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents detained a Honduran mother and her two U.S.-born children, ages four and seven, during a routine check-in in Louisiana. The younger child was receiving treatment for stage 4 cancer. Despite prior notice to ICE about the child’s critical medical needs, the family was swiftly deported to Honduras, without access to medication or a chance to consult their doctors. Legal representatives were blocked from contacting them, and the deportation was carried out before the courts opened, shutting down any legal intervention.

When we hear stories like this, most of us recoil in horror and ask: What’s wrong with these people? Who carries out such orders? And, how can anyone support a president who encourages it?

The answer that first springs to mind is simple: bad people. Because, by definition, bad people do bad things, right?

Not so fast.

A Surprising Historical Legacy

In the aftermath of World War II, the world struggled to understand the rise of fascism and the atrocities of the Holocaust. How had so many people come to support totalitarian regimes, participate in mass violence, or remain passive in the face of brutality?

At the time, many believed the answer lay in the presence of unusually bad or pathological individuals—people with deeply flawed or abnormal personalities. Working from this hypothesis, psychologists in the late 1940s set out to investigate what they called the authoritarian personality. In a landmark study, Theodor Adorno and his colleagues developed the F-scale (short for Fascism scale) to measure traits like submission to authority, hostility toward outsiders, rigid adherence to conventional norms, and preoccupation with power and toughness. Their goal was not purely academic: they saw this work as part of a broader effort to protect democracy by identifying the psychological roots of authoritarianism.

The results were striking. Authoritarian traits measured by the F-scale did indeed predict prejudice, ethnocentrism, and anti-democratic attitudes—but these tendencies were not confined to a small group of pathological individuals. To the researchers’ surprise, authoritarian dispositions were widely distributed across ordinary Americans, including middle-class people who appeared conventional, respectable, and well-integrated into society.

This finding revealed that the psychological vulnerability to authoritarian thinking wasn’t limited to an extremist fringe; it was embedded across the population, making the potential for political harm far more pervasive and unsettling than many had assumed. The study also exposed the limits of relying solely on personality traits to explain dangerous social behavior. As social psychologists absorbed these insights, attention gradually shifted toward investigating the external forces that shape human conduct—ultimately inspiring some of the most famous experiments in the field.

The first major experiments on obedience were conducted by psychologist Stanley Milgram, who set out to test whether—and under what conditions—ordinary people would follow orders to harm another human being. In his now-famous studies, participants were instructed to administer what they believed were painful electric shocks to a person in another room whenever the “learner” gave a wrong answer on a memory task. To the researchers’ astonishment—and often to the participants’ later distress—most people continued delivering shocks, even as the victim cried out in pain or fell ominously silent, simply because an authority figure in a lab coat urged them on.

A few years later, the Stanford Prison Experiment, led by psychologist Philip Zimbardo, placed college students in the roles of guards and prisoners in a simulated prison inside the Stanford psychology building. Within days, the “guards” became cruel and domineering, subjecting the “prisoners” to humiliation and abuse, until the study was shut down early for ethical reasons. These weren’t sadistic young men; they were ordinary students, specifically screened for psychological normality, transformed by the social pressures of their assigned roles and the surrounding environment.

Historical research echoed what psychologists were uncovering in the lab. Historian Christopher Browning, in his landmark study of a Nazi police battalion that carried out mass shootings in Poland, found that its members were not fanatics or ideological zealots, but middle-aged family men, drawn from everyday jobs, who descended into atrocity through conformity, peer pressure, and gradual moral desensitization. Similar patterns emerged in Hannah Arendt’s analysis of Adolf Eichmann, one of the architects of the Holocaust, whom she famously described as exemplifying the “banality of evil”—a bureaucrat more concerned with obeying orders and advancing his career than contemplating the human cost. Other scholars, such as Raul Hilberg, documented how clerks, railway workers, and civil servants across Europe became cogs in the machinery of genocide, not because they were inherently sadistic, but because of routine, hierarchy, and moral disengagement.

Of course, this isn’t to say that extreme psychopathology never plays a role in government-led atrocities. Leaders like Hitler, Stalin, and Mussolini displayed clear traits of psychopathy or sociopathy: grandiosity, lack of empathy, manipulativeness, and a hunger for domination. However, most of the people who carry out cruelty are not psychopaths. They are ordinary individuals swept up by loyalty, fear, social pressure, and the gradual erosion of moral boundaries. Without the participation of countless regular people, even the most dangerous leaders would have little power to destroy.

This is the enduring legacy of postwar research. It offers a powerful lens for understanding past and present atrocities, including the loyalty many show today toward Trump and his authoritarian movement, despite its cruelty. And it provides a sobering warning: when ordinary people stop questioning, stop resisting, and silence their better judgment, terrible things can happen.

What Actually Drives Their Behavior

The lessons of postwar research are as relevant today as they were in the aftermath of World War II. Human behavior is shaped not just by character, but by external forces. Decades of research reveal a layered set of forces that help explain what actually drives people’s political behavior today. Three stand out: group identity, cognitive dissonance, and deep social and emotional needs.

1. Group Identity

For most Americans, political identity forms early, usually by around age seven, long before we can critically evaluate parties, platforms, or leaders. Research on political socialization has consistently shown that parents are the strongest predictor of adult political affiliation and that partisanship is inherited much like religious affiliation. This early imprint shapes not only how people vote, but also how they see the world, which news sources they trust, and even what they define as right and wrong.

In recent years, party identification has grown much stronger. Political scientist Liliana Mason describes partisan identity in the U.S. as a “mega-identity” that overshadows other traditional group affiliations, including race, religion, and sex. As Mason argues, our political identities have become so fused with our social identities, cultural values, and moral worldviews that for many Americans, being a Republican or Democrat isn’t merely a political preference; it’s an expression of self.

Consider the 2016 election. Many Trump voters weren’t primarily drawn to his ideology, personality, or rhetoric; they backed him because he was the Republican nominee and, just as importantly, because they wanted to vote against the Democrats. For lifelong Republicans, casting a ballot for Trump often felt less like endorsing the man himself and more like standing with their political tribe—their family, community, faith, and values.

2. Cognitive Dissonance and Rationalization

Once people make a morally or politically charged choice, they face powerful internal pressure to defend it, even when the facts turn against them. Psychologist Leon Festinger described this in the 1950s as cognitive dissonance: the intense discomfort we feel when our beliefs, values, or actions collide. Instead of changing our cherished behavior or beliefs to resolve the inconsistency, we conjure justifications and rationalizations to ease our discomfort.

For example, Festinger’s research showed that when a doomsday cult’s prophecy failed to materialize, its most devoted members did not abandon their beliefs as expected but instead doubled down, inventing new justifications to explain away events and preserve their faith in the leader. This same pattern plays out constantly in political life, as people rationalize their own candidate’s mistakes while harshly condemning the missteps of others.

Psychologists Carol Tavris and Elliot Aronson expand on this idea in Mistakes Were Made (But Not by Me), describing the “pyramid of choice.” Once people begin justifying a small choice, they move down a path of escalating commitment. With each new decision comes greater rationalization, and the psychological cost of changing one’s mind grows.

Among Trump supporters, this dynamic has been visible for years. A voter who dismissed the Access Hollywood tape as “just talk” became more inclined to downplay later scandals. Someone who justified family separations at the border as “just enforcing the law” grew more determined to explain away subsequent abuses. With every step down the pyramid, turning back became harder.

3. Social and Emotional Needs

Some of the most profound forces shaping political behavior are social and emotional. Humans are wired not just for belonging, but for coherence, identity, and meaning. The drive for connection, acceptance, and a stable sense of self often runs deeper than any political calculation. For many Americans, political identity is not just about policies; it’s about family, community, faith, self-understanding, and a framework for making sense of the world.

This helps explain why breaking with one’s political tribe can feel like a form of social death. Research on political sorting, for example, shows that Americans increasingly organize their lives around partisanship—from the churches they attend, to the neighborhoods they live in, to the people they marry. For Republicans who have broken with Trump, the costs are often severe: loss of friendships, family estrangement, expulsion from social circles, and profound isolation. Public figures like Liz Cheney and Adam Kinzinger have not only been ousted from political power; they’ve been exiled from their social worlds. For everyday voters, the stakes can feel just as high.

But the challenge isn’t only social. Breaking ranks also carries a heavy emotional burden: the pain of admitting you were wrong. For many, this means reckoning with the possibility that they defended harmful policies or leaders. The guilt, shame, and regret can be crushing.

Even more profound is the disorientation that comes when a belief system collapses. Walking away from the political community that shaped one’s worldview forces a shattering self-examination: If I was wrong about this, what else am I wrong about? Who can I trust now?

Megan Phelps-Roper, who famously left the Westboro Baptist Church, has described how agonizing it was not just to lose her family and community, but her entire framework for understanding right and wrong. For those whose moral compass is tightly tied to a political movement, breaking away can trigger a profound existential crisis.

Finally, the costs are highest for those whose political commitments provide a sense of mission. Politics doesn’t just shape what they believe—it gives them purpose, a role to play in the world. To walk away is to risk losing not just an argument but the very thing that makes life feel meaningful.

Why This Matters

It’s tempting to believe that Trump supporters are simply bad people. If that were true, the solution would be straightforward: defeat or eliminate them. But the research we’ve explored here points to a much more challenging truth: what drives harmful political behavior is not evil personalities but ordinary human psychology.

And that has profound implications for how we respond.

When we misunderstand the problem, we end up using the wrong political strategy to achieve change, focusing on overpowering rather than persuading. We treat opponents as enemies to crush, rather than fellow citizens to engage in dialogue. We become less supportive of democracy, more willing to bend or break the rules to stop “the bad people,” and more accepting of political violence, telling ourselves that desperate times justify desperate measures.

The Path Forward

If we want to stop political cruelty, we have to let go of the fantasy that the world is divided into good people and bad people, and that the solution is simply to overpower the bad ones. Research on group identity, rationalization, and social belonging makes one thing clear: most harmful political behavior doesn’t come from bad people; it comes from good people behaving badly.

Understanding the forces that drive people to support harmful policies does not excuse their actions, but it does offer us a path forward. If we want to stop Trump and save democracy, we cannot afford to dismiss half the country as irredeemable.

Instead, we need to resist the pull of moral judgment and meet our fellow citizens where they are. By focusing on shared interests, addressing cognitive dissonance with compassion, and offering belonging without demanding immediate change, we create the conditions where transformation becomes possible.

That’s what Smart Politics is all about.

Which of the three explanations presented here best accounts for why many voters support Trump despite everything?

The Smart Politics Way is a free publication from political psychiatrist, Karin Tamerius, dedicated to teaching progressives how to communicate more persuasively with people across the political spectrum. Subscribe today to save democracy, one conversation at a time.

I'd add to this very insightful post that blinding political loyalties cut both ways. I used to reflexively presume that all consersative beliefs were rooted in disinformation. At some point, I began checking things out for myself and realized that I was wrong about certain things that my tribe takes as gospel truth. I now try to hold my opinions lightly until I've had a chance to hear from all sides, which includes doing my own fact-checking on what everyone is asserting.

Thank you for great post.

I often thought about some of the dynamics you described as I was navigating the most challenging aspects of several years of dealing with my health insurance company as I pushed back against their nonsense to avoid financial ruin. The banality of those customer service agents who could not have cared less if I was bankrupted or landed in the street. Or the VP who sent a letter that, effective immediately, kicked me out of the care of my specialist. The cruelty of it was remarkable. Zero empathy.

I chose to file complaints and insisted on speaking up and pushing back against the cruelty.

While it was no fun to endure - and I did prevail, fortunately - I am well aware that, ironically, it was good training for the unfolding times we're in now.

This is why I believe that it's important to take a moral stand along the lines of it not being right to treat anyone the way people are being treated as ICE carts them away. I think it's important to bring focus to the issues of humanity so that the callousness cannot completely take over. It's not about judging or characterizing folks who still support Trump; there's also cult mind control going on there and trauma binding, IMHO.

I think it's important to state loudly, clearly, and repeatedly that empathy is an important aspect of our national character. This is why we will not stand for more and more cruelty.